english class, chapter 3: entering the age of victoria, 1837-1865

the one where a thousand novels get published a year

This series is written and researched by myself and Sabrina, from the Middling Place. Our goal with this series is to give you a practical and theoretical understanding of Anglophone literature—this is our personal area of expertise. These practical tools are not exclusive to Anglophone literature; they will help you in a multitude of ways.

There is no better place to start in your journey to becoming a better reader than to read. So, at the end of every post, we’ll include some recommendations for both free-access and purchasable resources.

As always, this is a free resource that aims to democratize academic learning. We both have paid subscriptions turned on, but these posts will remain open-access. If you’d like to upgrade to paid subscriptions to support our work, you are welcome to do so.

Two weeks ago, I introduced you to the concept of realism in the novel. Last week, Sabrina wonderfully outlined the Romantic era and the Gothic. This week, we are stepping into that great and terrible world of the Victorians.

Before we dive into social and political contexts, let’s situate ourselves in the timeline. This week’s post covers what we’ll refer to as the early Victorian period, roughly spanning the years 1837-1865. This post was meant to cover the middle Victorian period, but it was so long my computer began to give out on me. Join us next week for mid-Victorian. Sabrina will be giving you the details of the high Victorian period following week.

Reader, I warn you: This is going to be a lengthy and detailed post. I cannot cover all of the early-Victorian era, but I am going to try my best to give you a good overview of the things I consider most important.

Put some music on, grab a coffee, sit down, and let’s begin!

—Emily

I. The Age of Victoria:

On the 20th of June, 1837, Queen Victoria ascended to the throne, following the death of William IV, her uncle. She was just eighteen at the time, and would go on to be known as one of the longest-reigning monarchs in history, dying in 1901. The Norton Anthology of English Literature tells us that:

“Her symbolic role was especially significant for members of the middle class who (however ironically) saw the most powerful woman in the world as sharing their core values…[she] encouraged her subjects to identify her with the highest qualities most often associated with the period in which she lived: earnestness, moral responsibility, and domestic propriety.”1

So, Victoria’s ascension aligns with something we’ve talked about over the last few weeks: the rise of a British middle class. Ideas like personal responsibility, self-reliance, hard work, and doing things for the social good all play a role in identifying rising middle class values. But there are a few things that pre-date Victoria’s reign I’d like to consider.

Reform

The 1832 Reform Act signaled a shift in the social standing of the middle classes. It created 67 new constituencies—meaning more representation in government; it broadened the definition of property ownership to include tenant farmers, smallholding land-owners, and shopkeepers; and, most importantly, it extended the vote to all men who owned property worth more than £10.

Though slavery had been abolished in the country of Britain in 1807, it was not until the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 that the British began “the slow move toward freedom” in the wider Empire.2 However, due to pressure from plantation owners, a four-year pause was instituted on the freeing of enslaved people—they were “apprenticed” instead, while plantation owners lobbied for compensation. While anti-slavery policies had been a huge point of social reform movements prior to Victoria’s reign, it was not until the year following her coronation that the 700,000 enslaved people in the British Caribbean were freed.

Railway Mania and Industrialization

Between the years of 1825 and 1850, Britain built 9,800 kilometres of railway lines.3

The first of these significant pre-Victorian railway innovations was the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester railway in 1830. This was the first steam-powered rail system in the world. In the years that followed—the Railway Mania years—the entire nation was transformed. The GWR connecting London and Bristol came in 1838, and the London-Birmingham line was completed. Trains were relatively accessible to all, too, thanks to handy class-based systems we still use today (first, second, third, fourth, etc.), meaning that in some cases, a train journey could be booked on an “outside” coach for about 3 shillings.

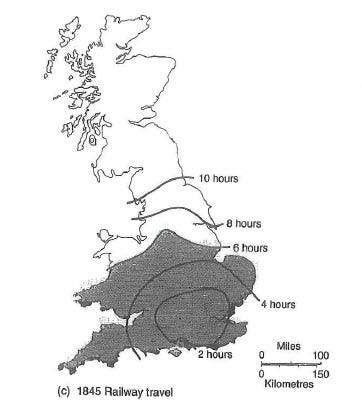

Think of it like so: In the 1700s, a journey from London to York by coach would take three days. In the 1840s, that time shrunk to ten hours.

Industrialization changed everything in Britain during these years, and I cannot begin to stress how absolutely bonkers it was to all of a sudden see the world shrink before your very eyes. With this industrialization came additional technological changes. By the time Victoria was entering her 22nd regnal year, Big Ben was completed; in 1863, the first London Underground train was built; in 1864, the British established Greenwich Mean Time—standardizing time for the entire globe.

Industrialization and mechanization meant that the country grew significantly. Cities like Manchester, Stoke-On-Trent, Birmingham, and Liverpool grew widely, with factory/mill work being the largest sources of employment for the working poor. The middle classes had new means to make money via these cities of industry, as well—they became clerks, schoolmasters, shopkeepers, accountants, etc.

II. Novels and the Public: The Middle Class, Leisure Time, and the Materiality of The Age

The rise of the middle classes in the 19th century all but ensured a rise in literacy. Middle class children were not working in factories or workhouses (things that would inevitably be regulated by early child-labor laws), but they were not educated in-home, either. While the landmark Education Act of 1870 was not passed until the mid-point of Victoria’s reign and education was not made compulsory until the late 1870s/early 1880s, literacy rates markedly increased prior to these things. Schools that were considered “affordable” to this new middle class cropped up everywhere.

The Middle Class and their Leisure Time

Katie Lumsden writes:

“Literacy rates increased dramatically in Victorian Britain, partly due to the growth of the middle classes, partly due to education acts making schooling more widely available. Parliamentary acts also cut down working hours in factories, and technological changes shortened the length of tasks both in and out of the home—which meant that, as the era went on, at least some Victorians had increasing amounts of leisure time.”4

We all of a sudden have this explosion in the growth of what is called the “Domestic classes.” These are the middle class people who did not work grueling hours in factories. They had free-time, they had gaslight in their homes—they had, for one of the first times in history, access to a print market that was all of a sudden affordable. Women—as you’ll know from part two—made up the majority of readers of fiction as they, too, could use their newfound solitary time to engage with literature.

The Materiality of the Age

As Sabrina told you last week, the early 1800s saw the rise of circulating libraries. Owning books was expensive, so places like Charles Mudie’s circulating library full of “family-friendly stock” (which charged subscription for about a guinea) were ideal places for people to get their hands on the latest volumes.

This was also the great-age of the newspaper. Dickens himself started life as a parliamentary reporter, and his work informed his ability to write toward a deadline. Serialization becomes the new way for fiction to be published in the early Victorian age. Dickens was a master of this, serializing his first novel, The Pickwick Papers (1836), in 19 episodes over 20 months. Pickwick was a roaring success, and catapulted Dickens—and the concept of serialized novels—to fame.

Serialization was cheap, too: issues cost about a shilling. The production and expense of reading was cheaper and more accessible. Not to mention, a narrative dispersed gradually creates suspense, and soon, the country (and world at large) were clamoring for more of Mr. Dickens’ novels.

Serialization also created jobs. This was the first point in England’s history where novelists could make money serializing fiction. Cheaper copies of books were sold at railways stations (there’s those all-important trains again!), and papers filled every newsstand. A rise in a middle class meant a rise in consumer culture. Books became mass-market objects—with cheap editions to be found by the 1850s. Authors, especially those like Dickens, were now celebrities.

III. Literature of the 1830s-1850s:

It wasn’t all sunshine and roses in the early years of the Victorian age, though.

The largely prosperous, early industrial years spanning 1832-1836 came to an end with the financial crash of 1837. Precipitated by “falling cotton prices, a collapsing land bubble, and fiscal and monetary policies pursued by individual actors and financial institutions in the United States and Great Britain,” the first decade of Victoria’s reign was marked by a global struggle.5 For the most part, the people impacted by this crash were the working poor. Cities like Manchester were hit the hardest by this—see our Norton: “workers and their families in the slums of such cities as Manchester lived in horribly crowded, unsanitary housing, while the conditions under which men, women, and children toiled in mines and factories were appalling.”6 It wasn’t just the economic bubble, either.

Corn laws, which placed high tariffs on imported grains, were especially detrimental.7 1845 saw a series of crop failures and the outbreak of the blight and later enforced famine in British-occupied Ireland, so they were eventually abolished. This did not help those already struggling—it is estimated that the Famine claimed one million Irish lives, and the slum cities of Manchester and Liverpool (to which many Irish refugees fled) still retained their economic hardships.

From these struggles came a series of novelistic innovations we know as the Condition of England novels.

The Condition of England Novel

The Condition of England Novel—situated squarely in the realist tradition—is also known as the “social problem” or “industrial” novel.

These novels, according to Dr. Andrzej Diniejko, “sought to engage directly with the contemporary social and political issues with a focus on the representation of class, gender, and labour relations, as well as on social unrest and the growing antagonism between the rich and the poor in England.”8

Importantly, the Condition of England novel arose from tensions surrounding the Industrial Revolution: they used the plight of the individual to represent larger social issues of the problems of rapid industrialization, poverty, and the lives of the working poor. Benjamin Disraeli’s Sybil, Dickens’ Hard Times, Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley, and Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South are all fine examples of this trend.

Let’s take a look at one of the earliest examples of the Condition of England novel, one that you might not have thought of: Oliver Twist (serialized 1837-39).

Oliver Twist is a bildungsroman-cum-Condition of England novel that follows the story of a young orphan raised in a workhouse, who escapes to London and joins a pickpocketing gang, led by the heinously anti-Semitic caricature, Fagin, and eventually he learns of his remaining family and lives happily as the adopted son of the kindly Mr. Brownlow.9

What makes Oliver Twist a Condition of England novel?

The Workhouse and the Orphan:

“Wrapped in the blanket which had hitherto formed his only covering, he might have been the child of a nobleman or a beggar; it would have been hard for the haughtiest stranger to have assigned him his proper station in society. But now that he was enveloped in the old calico robes which had grown yellow in the same service, he was badged and ticketed, and fell into his place at once—a parish child—the orphan of a workhouse—the humble, half-starved drudge—to be cuffed and buffeted through the world—despised by all, and pitied by none.”10

Oliver is an orphan—one of an estimated hundreds of thousands in 1830s England—and, surviving his infancy, his only options in life represent the struggle of all of those poor children: the workhouse, the pickpocketing gang (a life of crime), or death.11 In middle class, polite society, those who could not elevate themselves from poverty were seen as immoral, so the workhouses were created as part of the “Poor Law Amendments” of 1834.12

Social Classes:

As seen above, the “orphan of the workhouse” is to be “despised by all,” signaling a stark divide between those born into poverty and those lucky enough to be born out of it.

Labor, Criminality, and The Prison

“This was a vagrant of sixty-five, who was going to prison for not playing the flute; or, in other words, for begging in the streets, and doing nothing for his livelihood. In the next cell was another man, who was going to the same prison for hawking tin saucepans without license; thereby doing something for his living, in defiance of the Stamp-office.”13

Dickens points toward a major problem with Victorian poverty laws and the treatment of the impoverished classes: merely being poor could have you thrown in prison.

Oliver is eventually rescued from the fate of thousands of Victorian orphans, but the novel’s place as a Condition of England piece is undisputed. Dickens used his novels as a way in which to convey his concerns about the social issues plaguing his country, and having grown up partially in the workhouse (his father went to debtors prison), these issues were extremely vital to his writing. In his 1850 preface to the Cheap Edition, Dickens writes:

“Eleven or twelve years have elapsed since the description [of Jacob’s Island, a London slum] was first published. I was as well convinced then, as I am now, that nothing effectual can be done for the elevation of the poor in England, until their dwelling-places are made decent and wholesome.”14

Novels like Twist and Elizabeth Gaskell’s later North and South (serialized in 1855 by Dickens’ magazine, Household Words), helped awaken the middle and upper classes to the troubles of working poor and impoverished people.

In Gaskell, for example, the protagonist, Margaret Hale, leaves her hometown to join her family in the industrial city of Milton (a loosely fictionalizes Manchester), where she encounters factory workers and mill-owners, labour unionists and their families, as well as those whose lives were harmed by unsafe working conditions. Take this incredible passage:

““I think I was well when mother died, but I have never been rightly strong sin’ somewhere about that time. I began to work in a carding-room soon after, and the fluff got into my lungs, and poisoned me.”

[…]

“Fluff,” repeated Bessy. “Little bits, as fly off fro’ the cotton, when they’re carding it, and fill the air till it looks all fine white dust. They say it winds rounds the lungs, and tightens them up. Anyhow, there’s many a one as works in a carding-room, that falls into a waste, coughing and spitting blood, because they’re just poisoned by the fluff.”

[…]

“I dunno. Some folk have a great wheel at one end o’ their carding-rooms to make a draught, and carry off th’ dust; but that wheel costs a deal of money—five or six hundred pounds, maybe, and brings in no profit; so it’s but a few of th’ masters as will put ’em up; and I’ve heard tell o’ men who didn’t like working in places where there was a wheel, because they said as how it made ’em hungry, at after they’d been long used to swallowing fluff, to go without it, and that their wages ought to be raised if they were to work in such places. So between masters and men th’ wheels fall through. I know I wish there’d been a wheel in our place, though.””15

Bessy is the same age as our protagonist, Margaret, yet her life could not be more different: she was born poor, forced to labor in a factory, and dies in the novel because she has been exposed to such harsh conditions. Her father—the union leader—eventually is able to secure a good job, but not until he has lost everything first. Gaskell—though the novel ends in a romance plot—carefully weaves the suspense of romance with the sucker-punch of social critique, and does it incredibly well.

Condition of England novels, therefore, can be seen as not just fiction, but representations of the problems of the present—vehicles for critique, reform, and social conversation. They force the reader to engage with issues that are otherwise ignored—or invisible—to the upper classes. We find ourselves comparing the novels of this age with the novels of today: what kind of “condition-of-insert-country-here” modern novels can you think of? What kind of ways do the themes and individuals of Dickens and Gaskell come to represent a larger whole (a demographic, a city, a social problem)?

The Brontës: The Bildungsroman, The Governess, and the Gothic

Gaskell’s work brings me to a new point: that of the role of women authors in the era. Her first novel, Mary Barton, was published in 1848, only eleven years into the reign of Victoria. As women had been writing for over a century, this was not uncommon—but novelistic pursuits were still seen as masculine. Prior to Gaskell, in 1847, we see the first major publications of women’s novels of the Victorian age: the works of the Brontë Sisters.

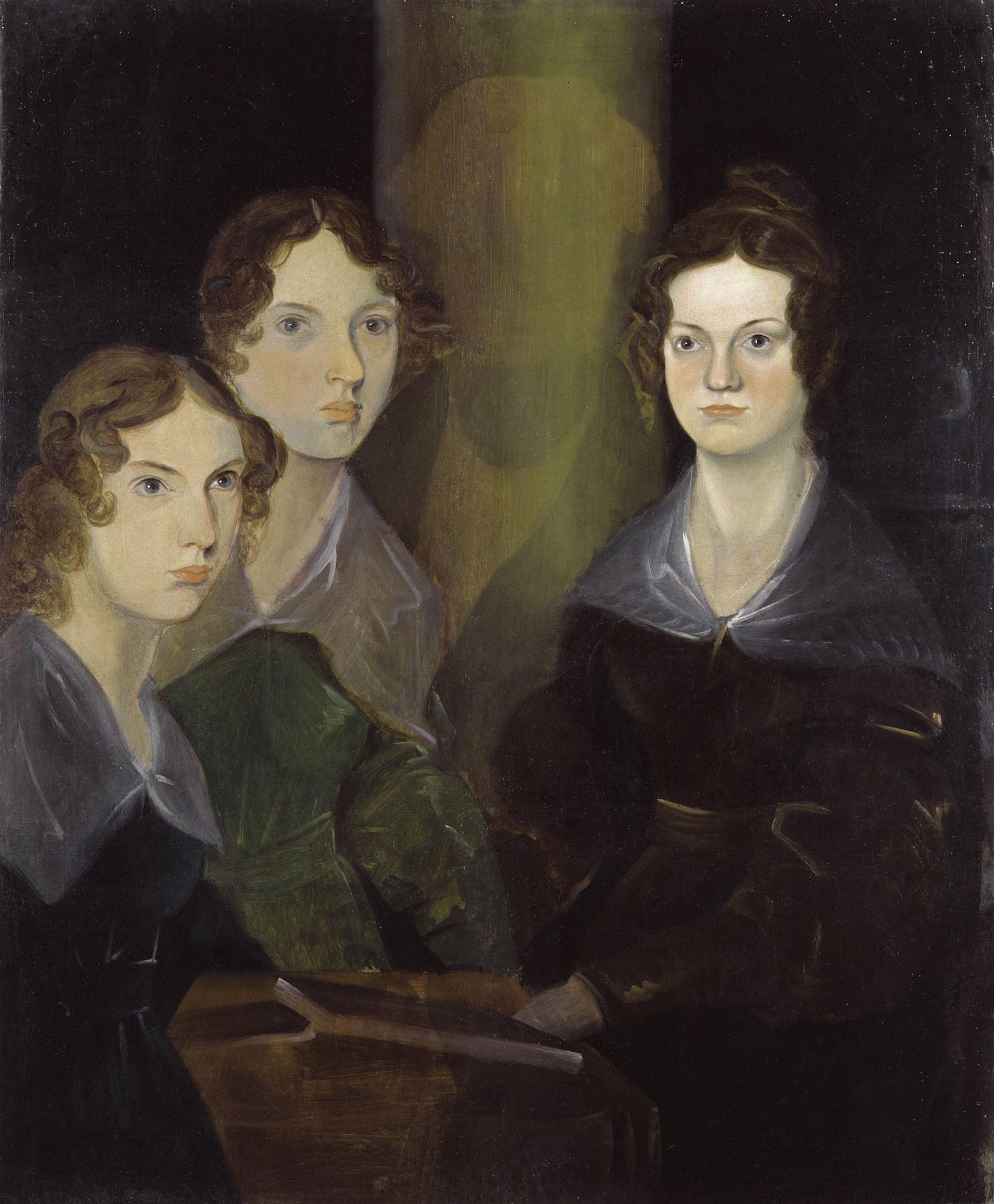

Writing under the pseudonymous titles of Currer, Acton, and Ellis Bell (male names), Charlotte, Anne, and Emily Brontë are possibly the most famous of the early Victorian writers. As the Romantic/Regency era had Austen, the early Victorian had the Brontës. Despite the fact that their first publication of poetry sold quite literally three copies, they were not discouraged from writing. Their first three novels, published in a three-volume set engaged with controversial problems, yet received (mostly) critical success.

1847: Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, and Agnes Grey

Charlotte’s novel, Jane Eyre is a bildungsroman that tells the tale of a young orphan (The Victorians did love an orphan) who leaves home, is educated at a fire-and-brimstone school, becomes a governess, and falls in love with her employer, the Byronic Mr. Rochester. The story features a lot more than that, but if you’ve never read it, I want to save you the spoilers.

What Jane Eyre did was situate an intelligent and plain young woman in the role of the explicator. Jane’s story is one in the epistolary tradition—older Jane tells the tale of her life from childhood in first person; the subtitle is “An Autobiography”—and she seeks to discover what it is that drove her to make the decisions she did. The novel takes elements of extant prose fiction, including Gothic tropes, and reworks them, creating a suspense-filled, beautiful story of a woman’s journey from dependence to independence. It engages with questions of Empire, propriety, love, passion, marriage, and infidelity. It speaks to levels of equality between men and women with a lucidity uncommon to the novels of Charlotte’s literary predecessors:

“I have as much soul as you,—and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you. I am not talking to you now through the medium of custom, conventionalities, nor even of mortal flesh;—it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God’s feet, equal,—as we are!”16

That the novel not only follows a female protagonist who falls in love with her much richer employer, but asks the question of what it takes to make that relationship work, as well as reinterpret the bildungsroman from a female perspective signals a major shift in the world of women’s writing. It is a tale of romance, to be sure, but it also questions what a woman’s role is in society—and how she may elevate herself without the assistance of a man’s wealth.

We are going to return to Jane Eyre in a later post on literary criticism—specifically, we will be looking at the novel in conjunction with postcolonial theory. Give it a read now so you familiarize yourself with it in advance.

Emily’s Wuthering Heights, like Jane Eyre, takes inspiration from the Gothic and the Epistolary, but it is far less tame. Criticized from the start for being too wild, too “savage,” this is a novel that takes the romance tradition and breaks it. Take this contemporary critical response from Graham’s Lady Magazine:

“How a human being could have attempted such a book as the present without committing suicide before he had finished a dozen chapters, is a mystery. It is a compound of vulgar depravity and unnatural horrors.”17

The plot is exceedingly complicated to explain, so I highly recommend that you just read the thing (linked above for free, as always). But there are narrative elements I wish to share that perhaps can point us in a valuable direction regarding how innovative it is.

The unreliable narrator: Nelly Dean and Lockwood both function as unreliable narrators. They make the plot intentionally complex; they omit information, they are motivated by their own self interests; they represent a class that perceives the residents of Wuthering Heights as lesser-than, as savage, wild.

Heathcliff: The foundling’s story is one that reflects back the Empire; it considers questions of madness, monomania, desperation, and the lengths to which people will go to take ownership over others.

Catherine: The ghost that haunts the entire text is a departure from realism. There is, however, still a blend of realist elements and the gothic in the text: we see stopwatches, clocks, and named-places; there are elements of “real life” in the narrative technique.

The will of the woman: Though she is problematic, Catherine’s headstrong and self-determined nature represents a new way of considering women in the novel. Not as morally resolute as Jane Eyre, Catherine Earnshaw is a wild and unencumbered woman.

The North not as a place of industry, but one of nature: The Brontë’s grew up on Romanticism. They loved the literature of Sir Walter Scott and the poetry of Byron. You see the influence of Romanticism in the depictions of nature, as well as in the Gothic tinge to the text. Emily was able to so seamlessly build upon and synthesize the two into her own representation of the Yorkshire moors, giving us a new way of considering nature in an age of industrial dominance.

There are similarities in the sisters’ novels: both engage with Empire, both consider madness, agency, and the idea of the orphan. Yet both are wildly different, as is Agnes Grey.

Anne’s novel sees similar ideas to Jane Eyre explored—the governess, the loss of fortune, empathy—but in its representation of the governess it differs entirely. Whereas Jane is capable of expressing herself, and eventually comes to find freedom through her labour, Agnes Grey positions the governess as oppressed, and the employer as oppressor. Though Agnes is able to rescue herself at the end and open her own school, it takes the question of women’s domestic and educational labour and considers it in relation to class, privilege, and isolation:

“The name of governess, I soon found, was a mere mockery as applied to me: my pupils had no more notion of obedience than a wild, unbroken colt. The habitual fear of their father’s peevish temper, and the dread of the punishments he was wont to inflict when irritated, kept them generally within bounds in his immediate presence. The girls, too, had some fear of their mother’s anger; and the boy might occasionally be bribed to do as she bid him by the hope of reward; but I had no rewards to offer; and as for punishments, I was given to understand, the parents reserved that privilege to themselves; and yet they expected me to keep my pupils in order. Other children might be guided by the fear of anger and the desire of approbation; but neither the one nor the other had any effect upon these.”18

Three novels, from three women—all of which set the stage for women’s writing in the era. Elizabeth Gaskell famously wrote Charlotte’s autobiography, and of the role of women’s writing, said this: “[Charlotte] especially disliked the lowering of the standard by which to judge a work of fiction, if it proceeded from a feminine pen; and praise mingled with pseudo–gallant allusions to her sex, mortified her far more than actual blame.”19

From the Brontës we see a literary inheritance that is considered one of the most important in English literature. I am not understating this. Whereas Austen’s social critiques were largely aimed at the marriage market, at the politics and particulars of her era, the Brontë’s provided a new means by which women could write: they were not confined to the spaces of marriage or social life, but instead were able to integrate those elements into wider conceptions of the world built around visions of the North of England, the gothic, the rural, the working woman, and the very notion of what it means to be educated.

These three novels do fall in the tradition of “realism,” but they do not quite represent the “real” in the way that the Condition of England novels do. As an exercise, consider what elements of realism differ between, say, Jane Eyre and North and South.

IV. Literature of the 1850s-1865:

We have established already that more books were being published in the early Victorian era than I think we could ever even read, so before we end for the day, I am going to give you a brief overview of some key novels and trends from the second decade of Victoria’s long reign.

The Condition of England and Realist trends continued into the 1860s, as we’ll see next week with some more Dickens and Middlemarch. But there are a few lesser-appreciated moves in fiction that I’d love to point us toward.

Thanks to a somewhat renewed interest in the Gothic, the now affordable cost of serialized texts, and the rise of consumer culture, mass-market novels became the desire of many a leisure-seeking middle class person. In particular, the Sensation novel became a widely-read, widely-loved item in the zeitgeist.

Sensation: Secrets, Lovers, and Ghosts

The sensation novel reached its peak between the 1850s-1890s and blended elements of gothic, the mystery, and what we now consider detective novels. These were pulpy, suspenseful, and—often—shockingly taboo. They combined tropes of Romance with the rawness of realism, and generally had a “secret” to reveal.

My favourite sensation novel is Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, a serialized, epistolary novel considered to be a proto-detective novel. I refuse to give you spoilers, so go ahead and give it a read…it’s brilliant. But, I will say, what it does borrow from the realist and social problem genre is its approach to the position of women in marriage at the time. As with most Victorian novels, it takes its unrealistic or often fantastical plot points and drives them toward a main concept of contention.

A famous novel of the genre is Lady Audley’s Secret written by Mary Elizabeth Braddon. While it plays upon taboo, it takes pains to explore the problems of the domestic sphere, engaging with ideas about women’s roles, marriage, and desire.

The Big Shift: Alice’s Nonsense and the Origin of Species

It would be irresponsible to acknowledge the major work of non-fiction that signals a shift in writing as we enter the mid- to high- Victorian era.

1859 saw the publication of On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin. The Victorian era was one of great expansion both industrially and scientifically, so it will come as no surprise that Darwin’s was just one of many, many scientific tracts published in the era. But it is perhaps the most influential piece of scientific writing to come out of the 19th century.

The theory of evolution—of survival of the fittest—will impact the writings of many of the later Victorians. It will become a point of discussion, of question—of thinking about who we are. Gone is the orthodoxy of Jane Eyre’s St. John Rivers and his ilk, and in its place comes a way of conceiving the world that is inspired by where we come from. Not in a Biblical sense, but an evolutionary one.

The final text I will be discussing today concerns children.

These are not the children of Dickens—who lead poor lives or are blameless orphans—but children who mark the new world of scientific and reasonable questioning. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) may be a children’s novel, and it might be nonsense, but it plays with many of the concerns that Victorians themselves grappled with.

The child has taken center-stage in much of our discussion. Oliver Twist, Jane Eyre, Catherine Earnshaw, Heathcliff, and even Agnes Grey all concern children in some way, shape, or form. The Victorians were fascinated by the idea that children were not just miniature adults, but individuals capable of thought, reason, and emotion (seems absurd, but it was a new idea).

The revolution that accompanied these new explorations in science, logic, mathematics, and reason are reflected in Alice’s insecurities about how she may solve the puzzles of Wonderland:

“I think you might do something better with the time,” she said, “than wasting it in asking riddles that have no answers.”

“If you knew Time as well as I do,” said the Hatter, “you wouldn’t talk about wasting it. It’s him.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” said Alice.

“Of course you don’t!” the Hatter said, tossing his head contemptuously. “I dare say you never even spoke to Time!”

“Perhaps not,” Alice cautiously replied, “but I know I have to beat time when I learn music.”

“Ah! That accounts for it,” said the Hatter. “He won’t stand beating.”20

Alice and the Hatter might be talking nonsense, but if we go back to the very beginning of this post—where I talked about trains—we can put a few things into perspective. Time, once conceived as reflective of a world created in seven days, has been reconceived. Not just by Darwin’s ideas of evolution, but by the industrial revolution. Standardized time—that is, time regulated throughout the country and Empire—has become the norm. Workers are now regulated by a working day; trains run on a set timetable, and Alice, the child, knows nothing else. The Hatter then suggests a tension—one between this new way of viewing the world and the old ways. Carroll was, after all, both mathematician and Anglican deacon.

V. Concluding

Early Victorian novels set the stage for what we now consider the “Modern Novel.” (Again, not to be confused with the Modernist Novel.) Narrative techniques, ideas of plot sequencing, tropes, and readerly engagement that we still utilize today borrow from the vast wealth of literature published in just Britain in the 19th century. If we were to consider non-Anglophone novels (in a different series, eventually) or even just American novels, we would see that the world then and the world today might be entirely different, but literature has always served a social function. The books we looked at today critique, they call attention to, they pander to, they capitalize on reader expectation—and often, subvert it.

We cannot consider the future of the novel today without at least considering its past. We read because we wish to know ourselves—to learn about the world—just as our literary forebears in 1845 did. Just as Dickens wanted to call attention to social horrors, so too do James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Kazuo Ishiguro, Khaled Hosseini. The list goes on.

The City of London and the Nation of Britain became the place where novels were conceived, where they were situated. We will talk more about it next week, but for now, take a moment to consider how time and space are figured in these novels. How can you see the effects of the industrial revolution? How might we see the effects of our technological revolutions in today’s literature?

We’ve talked about a lot today, and we have barely scratched the surface of the early Victorian era. There are thousands of directions I could have taken this in, yet in an attempt to provide you with open-access resources and shorter novels, I’ve covered just a handful of movements, styles, and themes.

Let’s review:

I. Victoria

The Victorian age spans 1837-1901. It is marked by rapid industrial expansion; huge population growth; a burgeoning middle class; and an increase in consumer culture, literacy, and schooling.

Her reign marks the “end” of the Romantic era, but it does not mean Romantic sensibilities are entirely abandoned. Authors like the Brontë sisters still engage with and utilize Romantic tropes in their work.

II. The Rise of the Middle Class and Serialization

The middle classes had more leisure time than their predecessors, thanks to changes in the workforce and new middle-class jobs. Education—specifically schools aimed at educating the middle classes—increased literacy rates exponentially.

This leisure time enabled them to read more, read widely, and read affordably.

This affordability came in the form of serialization and circulating libraries. Serialization made novels as cheap as bread—as each issue only cost about a shilling.

Train stations and public newsstands now stocked mass-market novels, serial periodicals, and newspapers, where people who used the new means of travel could easily access literature—something that kept them busy on train rides!

Women in particular made up the readership of most novels, as for one of the first times in history, a new class of domestic women had down time in which they could read.

III. The Novel 1830-1850

A major shift in the novel at this time is the so-called Condition of England novel, which aims to expose social problems to the reading public.

Condition of England novels are within the realist tradition, utilizing individuals and typically third-person narratives to stand in for the wider social group.

Examples include Oliver Twist, Hard Times, North and South, Sybil, and Shirley.

Women authors are becoming both more prevalent and more widely acknowledged. Next week, we will discuss George Eliot—possibly the most famous Victorian writer of the later half of the Victorian period—whose novels truly set the stage for the women writers of the early 20th-century.

Examples include the oeuvre of the Brontë sisters and Elizabeth Gaskell’s works.

IV. The Novel 1850-1865

We meet the Sensation Novel, a direct offshoot of the demand for mass-market books. These novels take the realist tradition and suffuse it with narratives about social taboos such as desire, lust, murder, and crime. Considered a precursor to the Detective Novel of the late-Victorian period.

Examples include The Woman in White and Lady Audley’s Secret

The publication of On the Origin of Species signals a shift in Victorian worldview. Religious orthodoxy is questioned; science becomes a major element of late-Victorian fiction; and the notions of who we are begin to change.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland marks a move toward a non-realist perception of the child—as opposed to Dickens—and plays with the notions of time, space, and scientific reasoning.

This is your bare-bones literary history. Later on in the course, we will pick out some examples of texts mentioned here and use them as vehicles to explore literary criticism. Specifically, we will look at how theory and criticism utilize the Victorian novel in particular.

For now, I leave you with another optional assignment:

Read one of the books I mentioned today.

Just read it. If you’ve never read it, give it a go. If you’ve read it before, read it again.

Take some time to switch off and see if you can notice any of the themes or ideas I talked about today. In the meantime, I am off to do my homework and finish the mid-Victorian post. (Sneak preview: We’re going to be starting with Dickens again, and we’ll finally meet George Eliot.)

See you soon

—Emily

As always, all the resources linked throughout the post are free via Project Gutenberg.

Here are some free and some purchasable recommended readings:

Jane Eyre - Charlotte Bronte

Wuthering Heights - Emily Bronte

Great Expectations - Charles Dickens

The Woman in White - Wilkie Collins

The Mill on the Floss - George Eliot

The Cambridge Companion to the Victorian Novel (linked here)

Atlas of the European Novel - Franco Moretti

The London Underworld in the Victorian Period: Authentic First-Person Account by Beggars, Thieves, and Prostitutes - Henry Mayhew and Others

The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Shorter 11th Edn., Vol. 2, General Ed. Stephen Greenblatt, p. 510

The Norton, p. 512

Charles More, The Industrial Age: Economy and Society in Britain, 1750-1985 (Harlow, UK: Longman Group, 1989), 91.

Katie Lumsden, “How the Victorians Created the Modern English Novel,” https://lithub.com/how-the-victorians-created-the-modern-english-novel/

Stephen W. Campbell, “The Transatlantic Financial Crisis of 1837.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History (March 2017) https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acrefore-9780199366439-e-399.

The Norton, p. 513

Corn in this context refers to wheat and other grains/cereal crops.

Dr Andrzej Diniejko, “Condition-Of-England Novel,” https://www.victorianweb.org/genre/diniejko.html

to read more about the representation of Fagin and Dickens’ anti-Semitism, click here: https://web.archive.org/web/20081205101924/http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/dickens-greatest-villain-the-faces-of-fagin-509906.html

Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, Chapter 1

Read more about the Victorian poor here: https://editions.covecollective.org/chronologies/life-poor-victorian-england#:~:text=During%20the%20Victorian%20era%2C%20the,and%20lack%20of%20stable%20employment.

https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1834/jun/09/poor-laws-amendment-committee

Oliver Twist, Chapter 13

Dickens, Preface to Oliver Twist: The Cheap Edition (1850)

Elizabeth Gaskell, North and South, ed. by Patricia Ingham (London: Penguin Classics, 1995), 102-103

Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, ed. by Margaret Smith (Oxford: World’s Classics, 2000), 253

Nick Collins, “How Wuthering Heights caused a critical stir when first published in 1847.” https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/8396278/How-Wuthering-Heights-caused-a-critical-stir-when-first-published-in-1847.html

Anne Brontë, Agnes Grey (Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Classics, 1998), 22-23

Elizabeth Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Brontë, Vol. 2: https://cdn.britannica.com/primary_source/gutenberg/PGCC_classics/lifebronte2.htm

Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking-Glass (New York: Modern Library, 2002), 60

Emily, though I signed up for your class at the beginning, life didn't allow me to start until this post. Is there a way to read the previous ones?

The Victorian (and Edwardian) era is my research area as a Historian and you’ve done a brilliant job of conveying the key points of the lengthy era. Well done! ☺️